A project is under way, led by Sylvia Holton and William S. Peterson to reconstruct the personal library of William Morris. The books that once belonged to Morris were largely dispersed through various sales after Morris’ death, including some acquired by what are today still the two largest holdings at the Wellcome Library in London and the Morgan Library in New York. The catalogue — a work in progress – and further details about the project can be consulted online at this location.

The University of Lincoln is launching “Tennyson in His Library: Reading, Writing, and Collecting Books in the Nineteenth Century”, an interdisciplinary project set up by the School of Art and Design and the School of Humanities.

This project is devoted to a study of the private libraries held at the Tennyson Research Centre (TRC) in Lincoln of the poet Alfred Tennyson, his wife Emily Tennyson, his father George Clayton Tennyson, and his uncle Charles Tennyson d’Eyncourt offer. The ambition is to gain:

insight into the social, cultural, and intellectual history of books and of reading in the nineteenth century. The project will seek to develop social conceptions of reading, giving us a sense of the way that Victorian readers exchanged as well as absorbed texts. It will also utilise Lincoln’s research strengths in materials analysis, conservation, and restoration in order to adapt forensic methodologies to the study of the book.

The project will fund a full-time PhD student who will be encouraged to develop his or her own research project. But areas of interest that might be explored include:

- Tennyson’s libraries and the communications circuit (writing, illustrating, printing, publishing, selling, reading books in the period)

- Family libraries and the history of reading

- The private library within nineteenth-century print culture

- The library and the nineteenth-century collection

- Material texts and Tennyson’s oeuvre

- Tennyson as annotator

- Manuscript and print: Tennyson’s proofs

All inquiries about the project and the studentship may be directed to Dr Jim Cheshire.

Stephen Gregg, who delivered a paper at Writers and their Libraries on “Virtual Conversation in the Library of Bishop Richard Hurd”, has blogged about his work on the Hurst library at digitalhumanistbeginner.

Delegates who are coming to London for the Writers and their Libraries conference may be interested in a free talk on the life and library of the actor, author and producer Malcolm Morley (1890-1966) by Professor Michael Slater (Birkbeck College) and Jonathan Harrison (Senate House Library). Morley’s library and archive, which were donated to the University of London by his family, sheds light among others on his work on the Ternan family and stage adaptations of Dickens’s work. The talk will feature a small display of items from the collection.

The talk will take place on 13 March, from 6 to 7pm, in the Seng T. Lee Centre in the Senate House Library. All are welcome, but booking a space is necessary. Please contact shl.officeamdin[at]london.ac.uk.

Here is a blog post that is worthwhile reading by Claudine Moulin on Fascinating Margins. Towards a Cultural History of Annotation over at annot@tio. She points out that “annotations and other reading traces play a special role from the point of view of cultural and linguistic history, yet, up to now, they have not been analyzed in a greater context regarding their functional means as well as their textual and material tradition”. To remedy this, she is writing a book that “aims to study the cultural and historic dimension of annotating texts taking into account wide ranging interdisciplinary aspects”. She plans to draw up a typology “of the wide variety of annotations which are in evidence since the Early Middle Ages” and to trace the changes and transformations that have taken place since then an up to “the modern digital age”. She will not stop at the European tradition, however, but also draw on annotation practices in other cultures from the Arabic and Asian world. This is a book we certainly all look forward to.

Guest post by Richard Oram

Although my own institution, the Harry Ransom Center, has one of the largest collections of Anglo-American authors’ libraries (arbitrarily defined as 50 or more books belonging to a given writer), several years ago, I found that we didn’t have a listing of them (a problem that has since been rectified.)

It soon became apparent that curatorial staff in other large research libraries more often than not didn’t know how many such libraries they owned. As a result, Joseph Nicholson, a cataloger at Louisiana State University, and I sent out a survey to special collections in the U.S., U.K., and Canada. We also began searching likely library catalogs and web sites, discovering in the process that there are many inconsistencies, to put it mildly, in provenance cataloging.

Despite various obstacles, we have assembled a listing of information about more than 500 libraries (primarily English and American authors), to be published next year by Scarecrow Press. But there are so many gaps in the data! This is why I will be furiously taking notes at the Writers and their Libraries conference. Our survey response rate from the U.K. was quite low, so we would be particularly grateful for additional information from British institutions; please contact me (roram[at]austin.utexas.edu) if you think you might be able to contribute to the project.

Guest post by Karen Attar.

As soon as the “Writers and their Libraries” conference was announced, Senate House Library knew that it would like to support it with a display. Then our treasures volume was published, and it was clear that our major exhibition for the period from January to mid-July 2013 would need to support the treasures book. Luckily it was possible to do both at once: to feature items from the treasures book that were part of writers’ libraries, supplementing them with other books that showed the people featured both as writers and the owners of libraries.

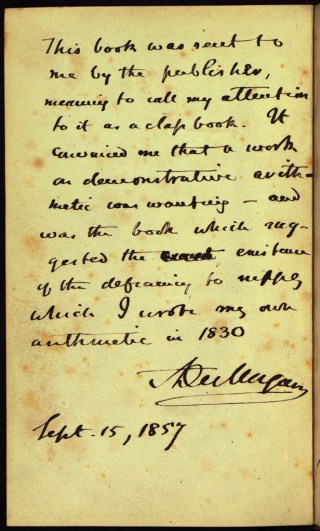

Note by Augustus De Morgan on front flyleaf of John Bonnycastle’s The Scholar’s Guide to Arithmetic (1828)

The section on “Writers and their Libraries” features five writers: Thomas Carlyle, Augustus De Morgan, George Grote, Walter de la Mare, and Harry Price. Thomas Carlyle stands out because his books – and the books he annotated, which were not all his – are to be found in various places. The exhibition pièce de resistance is a borrowed copy of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh, which Carlyle annotated acerbically throughout. The other four writers are all men with substantial collections now held at Senate House Library. Carlyle and Grote having been historians, De Morgan a mathematician, and Harry Price a psychical researcher, Walter de la Mare is the only literary writer among the group. The edition of Peacock Pie displayed shows his alterations for a new edition; more generally, the books by others owned and annotated by him say more about his library. Grote is represented by his most famous authored book and one of the visually more striking books he owned – albeit not annotated by him, as Grote generally made his copious comments about his reading in separate notebooks (some transcribed in his wife’s biography and recorded in the Reading Experience Database). He and De Morgan created Senate House Library’s founding collections. Unlike Grote, De Morgan – considered by some to be the greatest mathematician of his time – did annotate his books, often quirkily, and was renowned for doing so. His habit emerges clearly in the three displayed, one of which inspired his own textbook on arithmetic. Harry Price publicised his library more than most, by publishing specifically about it. My favourite of the four books shown here is Angelo Gambiglioni’s treatise on criminal law Tractatus de Maleficiis (1508), included in Harry Price’s exhibition catalogue of 1934 (also shown). Price misdated the book to “ca 1490”, I think wilfully in order to class it as an incunable.

All conference delegates are warmly invited to visit the display on “Writers and their Libraries”, a sub-set of our treasures volume, on the fourth floor of Senate House, during standard library opening hours, and also the smaller display in the Jessel Room annex on the first floor of Senate House.

Guest post by Stanton J. Linden

Folio 1 of MS Sloane 1346 in the British Library opens with these words by Henry Power: “A Catalogue of all my Bookes taken this 1st of September 1664 just before my removeall [from Halifax] to Wakefield.” On the fifteen folios that follow, Power copied out in “hasty hand,” the contents of his personal library, supplying brief entries, usually only the author’s last name and an abbreviated title for each of the 543 books. Within the Catalogue, books are organized in sections only by size and the language in which they were written. There is no classification by subject or alphabetical listing by author. Since this is a physician’s collection, medical books in Latin—often by foreign authors and published abroad—are predominant. Clearly, this is a text intended for private use, not posterity. The fact that it was hidden away in manuscript and that Power himself—at least later in life—might be said to have been “hidden away” in remote Yorkshire also contributed to the fact that his achievements have often been overlooked.

With focus on my transcription of Power’s Catalogue and related study and annotation, I hope my study will reveal the importance of this previously unknown text to our understanding of early modern medical education and practice, the book trade, especially in rural England, as well as the role that his library played in the life of this rural doctor. Note: I have added the following “modern” subject classification scheme to the transcription to facilitate study and conversation. Those interested in the topic might give it a swift perusal since I will be referring to several of these subject classes, but have neither time nor interest in making this a statistical presentation.

|

Subject Classification: Henry Power’s Catalogue |

|||

|

|

|

Number of books |

% of total |

|

AHIS |

Ancient History |

18 |

3.3 |

|

ALCH |

Alchemy |

22 |

4.0 |

|

AST |

Astrology and Astronomy |

19 |

3.5 |

|

BIB |

Bibles |

13 |

2.4 |

|

BOT |

Botany, including Herbals |

16 |

2.9 |

|

CLIT |

Classical Literature: all genres |

28 |

5.1 |

|

CMED |

Classical Medicine and Science |

10 |

1.8 |

|

CONT |

Controversies |

12 |

2.2 |

|

EDUC |

Education, Practical Arts, Invention |

15 |

2.7 |

|

EMH |

Early Modern History, incl. Heraldry |

11 |

2.0 |

|

EML |

Early Modern Literature: all genres and Rhetoric |

36 |

6.6 |

|

EMM |

Early Modern Medicine, Anatomy and Surgery |

97 |

17.8 |

|

EMSC |

Early Modern Science and Natural Philosophy |

33 |

6.0 |

|

FRN |

Books written in French |

9 |

1.6 |

|

GEOG |

Geography, Travel, Exploration |

21 |

3.8 |

|

LAW |

Law and Legal Affairs |

13 |

2.4 |

|

MATH |

Mathematics |

11 |

2.0 |

|

MISC |

Miscellaneous Identified References, e.g. Music |

7 |

1.2 |

|

OCLT |

Occult, Magic |

9 |

1.6 |

|

PHIL |

Philosophy and Logic |

40 |

7.3 |

|

PHRM |

Paracelsus, Iatrochemistry, Pharmacy |

15 |

2.7 |

|

POL |

Politics and Government |

10 |

1.8 |

|

REF |

Dictionaries, Lexicons, Grammars, etc. |

21 |

3.8 |

|

REL |

Religion, Theology |

33 |

6.0 |

|

XX |

Unidentified References |

24 |

4.4 |

|

|

Total number of books |

543 |

|

Adam Smyth, one of the speakers at our conference, has contributed to the LRB Blog on Milton’s lust, and other marginalia.

Guest post by João Dionisio

In the Gospel according to John, Nicodemus heard Jesus say that no one could see the kingdom of God unless through rebirth. Nicodemus reacted with puzzlement for it seemed to him that no one, once born, would be able to be born again (“How can anyone be born after having grown old? Can one enter a second time into the mother’s womb and be born?”, John 3:4, New Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition). Jesus then replied: “no one can enter the kingdom of God without being born of water and Spirit. What is born of the flesh is flesh, and what is born of the Spirit is spirit.Do not be astonished that I said to you, ‘You must be born from above.’ The wind blows where it chooses, and you hear the sound of it, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit” (John 3: 5-8). Here lies the basis for baptism, one of the seven sacraments in Roman Catholic Church which came to be associated with the assumption of a (new) name. The motive of regeneration or rebirth plays a core role in the poetics of Portuguese writer M. S. Lourenço (1936-2009), in the guise of a current literary motif, under the paratextual form of a made-up obituary or more visibly through the instance of his alter ego Alexis Christian von Rätselhaft und Gribskov. Known as the fictional author of O Doge, a collection of prose short pieces published in 1962. Though it is not the only, it is certainly the most conspicuous alternative name inscribed on the title page of several books in Lourenço’s private library. These books may function as a biographical trait ascribed to the ‘Alexis von Gribskov’ persona : what kind of books did he have? which books did he read? and so forth. By looking into this part of his library, we can shed on some aspects of Lourenço’s literary work from the 1960s. Perhaps more importantly, looking into this part of his library enables one to view it as the stage where multiple personal projections enter in an intellectual dialogue. Against this background emerges the seemingly special status of some books by Rilke, both as a determinant factor in the literary staging of otherness and as a possible poetic enactment of the Gospel passage: “the wind blows where it chooses”. In this respect the fact that Alexis von Gribskov’s motto is precisely “spiritus ubi vult spirat” is especially meaningful.

The reason why we are putting together this conference on Writers and their Libraries has become apparent (as if it needed any elucidation) from an article in The Guardian website today by freelance writer Wayne Gooderham on “The Secret Contents of Second Hand Books”. A collector of annotated books and regular blogger on the subject, Gooderham explains how he’s got second hand booksellers in London keeping an eye out for him for whatever may be of interest. Collecting books with personal inscription is one thing, he says, “find the buggers” another. To his delight, the manager of Skoob Books invited him along to their warehouse near Oxford, to browse around but also to look at their collection of items they had over the years found in books. Mostly the objects are nothing extraordinary: book marks, tickets, postcards, photos, pressed flowers (a tradition that seems not quite to have disappeared), and so on. But the tantalizing presence (and preservation) of past human activity of the most ephemeral kind is what is fascinating. Equally fascinating are the (at the time of writing this) 146 responses that readers have posted in the comments section. Finding “any old crap pleases” apparently, and it is more popular than we had imagined. At least one other blogger, who works as a rare book cataloguer, is keeping a list of these objets trouvés.

Gooderham has put together a small exhibition with items from the Skoob warehouse in Foyles on Charing Cross Road. The exhibition ends on 13 December, so you can still catch it. Otherwise you can check out the small selection of his favourite items Foyles have made available on their website.