Registration for the Writers and their Libraries conference is now open. The registration fee is £65 (full fee) and £45 (reduced fee for speakers at the conference, registered students and members of the Institute of English Studies. To register please follow the link to the on-line registration page. A preliminary programme is available from the Institute website.

An interesting post from the Finding Shakespeare site about inscriptions in the holdings of the Royal Shakespeare Company researched by Jean Christophe Mayer (Montpellier University).

Guest post by Tim Pye, Curator of Early British Literature, The British Library

The British Museum Library of the eighteenth century thrived on the private collections of books amassed by eminent bibliophiles. The names of Hans Sloane, George Thomason, Clayton Cracherode and David Garrick will be familiar to researchers using the Library’s early printed collections. Many thousands of the pre-1800 books still used today arrived at the Library as a result of the donation or purchase of the aforementioned gentlemen’s personal libraries.

The majority of the Library’s early named collections have been the focus of study and research, and many have accompanying catalogues and lists; however, there is one exception. In 1786 a collection of between 800 and 900 books was bequeathed to the Library. These books, chosen by Cracherode and Robert Tyrwhitt (1735-1817), were marked with an inscription on the fly-leaves and then dispersed throughout the Library’s burgeoning collections. No list was created (or, at least, none survives to this day) and the bequest – by Thomas Tyrwhitt – appears to have been largely forgotten.

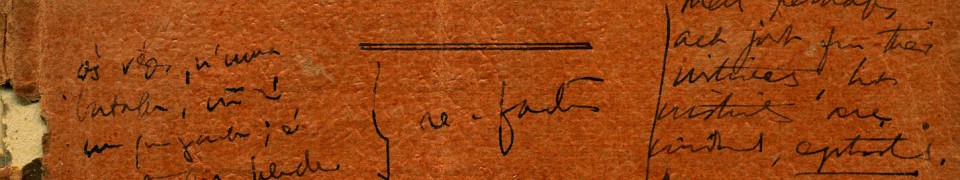

The flyleaf of Tyrwhitt’s copy of Ammianus Marcellinus’s Rerum gestarum (Parisiis, 1681 – BL shelfmark 586.k.12).

Thomas Tyrwhitt (1730-1786) was one of the most prominent scholars of the second half of the eighteenth century. Considered by some to be the first modern editor of Chaucer, Tyrwhitt contributed to the great editing of Shakespeare undertaken by Steevens, Johnson et al, and was key to debunking Thomas Chatterton’s Rowley creations. His learning appears to have known very few bounds, as summed up in Nichols’s Literary anecdotes (1812):

“Besides a knowledge of almost every European tongue, he was deeply conversant in the learning of Greece and Rome. [… ] He was thoroughly read in the old English writers; and, as his knowledge was directed by a manly judgment, his critical efforts have eminently contributed to restore the genuine text of Shakespeare. The admirers of Chaucer are also greatly indebted to him, for elucidating the obscurities, and illustrating the humour, of that antient Bard.” (Vol.3, p.147)

Tyrwhitt’s personal collection of books must have been extensive and rich in early European and British volumes. We are probably unlikely to ever know the extent of his entire library but we do know that a proportion is located, and can be identified, at the British Library. I have therefore taken on the daunting (some would probably say foolish!) task of trying to recreate the Tyrwhitt bequest. Without a list of the books clues have to be sought out elsewhere; for example, in his published works or his extant papers. Slowly but surely a picture of the library of this great man of letters is beginning to form, providing us with a glimpse into his scholarly workings and an insight into the early growth of the UK’s national library.

At the Writers and their Libraries Conference I will discuss what I have been able to discover about Tyrwhitt’s books so far and talk about the methodology involved in trying to locate what is a relatively tiny collection of books in a repository the size of the British Library.

A guest post by Stephen Gregg

My work discusses reading experiences and scholarly practices as revealed in the commonplace books and the annotations in the printed books held in the library of Bishop Richard Hurd (1720-1808). Hurd was an important contributor to eighteenth-century English literary history. His library, located in the old Bishopric of Worcester palace, Hartlebury Castle, still exists almost unchanged today. The collection, which was built up in his own lifetime, consists of over 3,000 titles and includes gifts from George III as well as substantial portions of the libraries of Alexander Pope and scholar William Warburton. Both Hurd and his library are very under researched (see only Cartwright, unpublished thesis, 1980; Penney, 2011).

Importantly, Hurd’s interaction with his library was not as a lone scholar, for he was engaged in a form of dialogue with those books and particularly with the other users of those books. The eighteenth century prized conversation as medium by which contention and social cohesion was negotiated within a variety of cultural networks (see for example, Goldgar, 1995; Mee, 2011); moreover, reading was often compared to conversation, as Robert Bolton noted ‘We may be said, with equal propriety, to converse with books, and to converse with men’ (1761). Hurd’s commonplace books held at the library are a lifetime’s observations on literature, religion and politics: but they are also an active and reflective dialogue with books. In addition, Hurd owned books previously owned and annotated by Pope and Warburton – books that are then annotated by Hurd; and his nephew, Richard Hurd (Jnr.) acted as secretary, copying out Hurd’s notes, the annotations by Warburton and even making his own notes. I argue that, taken together, they amount to a virtual conversation. It is a conversation that spans different lifetimes and that reflects a variety of reading experiences, cultural affiliations and political positions and is all the more remarkable for taking place within the space of a single collection of books.

A guest blog by Victoria Pineda

My contribution to the Writers and their Libraries conference deals with the library of Antonio de Solís y Rivadeneyra (1610-1686). Solís was a high official of Philip IV’s Secretary of State, and a well known poet and a playwright. When he was appointed as royal chronicler of the Indies in 1661 he gave up the writing of poetry and drama to undertake research for the Historia de la conquista de México(History of the Conquest of Mexico), which would not be published until 23 years later, and was to be received great success in Europe and the Americas. The wages he received as royal chronicler were added to his other two salaries as secretary tothe King and second official of the Secretary of State, which secured him a stable position and allowed him to enhance his home with books, paintings, jewels and tapestries.

His nineteen-door bookcases kept about 1,500 volumes, and the collection is considered to be among the richest private libraries in Golden Age Spain. The volumes have not been located, and may not survive, but the “post-mortem” inventory of the books in the library offers a unique insight into what was there. After Solis’ death, a bookseller named Anisson made a detailed survey (one of several inventories made of all of Solís possessions according to class of object — paintings, clocks, chasubles, etc. — prepared by several specialists) of Solis’ books. As he usually recorded the name of the autor, (part of) the title, the language, format and price, and also whether the book contained illustrations or not, it is posible to reconstruct what Solis was Reading, though the exact edition may not be known.

Anisson’s appraisal of the library suggests that while Solís did not particularly care for fiction (although he did own the standards of the time), he had a keen interest in history, politics, history-writing handbooks, dictionaries, military treatises, geography, religion, and quite a few other disciplines. Several significant conclusions may be drawn from the analysis of the inventory of this multi-lingual, multi-disciplinary library. Firstly, an examination of the general household inventory, which contains the library appraisal, allows us to imagine some of Solís’s “protocols of Reading”. (I borrow Robert Scholes’s term to refer to the material setting of the act of reading and writing.) Secondly, it allows us to argue that Solís collected books as an affirmation of his own self and of his professional status (one of the three categories of private libraries in the early modern period, according to Valentino Romani). Thirdly, the catalog also suggests that Solís conceived the writing of history as an art where erudition and rhetoric played equally important roles at a time when the foundations of a new kind of history, more “scientific” or “critical”, were being laid. Lastly, a consideration of the books Solís owned readdresses an issue that has been almost completely neglected by historians and critics, namely, the interpretation of Solís’s History of the Conquest of Mexico as a work with a high political content, where the figure of Hernán Cortés is presented to the King, to whom the book is dedicated, as a sort of Machiavellian hero, at a time of such great political, social and economic distress as were in Spain the two last decades of the seventeenth century.

Readers might be interested in two call for papers on marginalia in eighteenth- and early nineteenth century German literature. One is for the North Eastern Modern Language Association, 21-24 March 2013 in Boston; the other, sponsored by the North American Goethe Society, is for the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies, 4-7 April 2013. More information is available on the cfp.english.upenn.edu list.

Patrick Spedding of the Centre for the Book at Monash Univesrity recently posted a list on his blog with terminology used to describe annnotations in books. The list, he promises, is a work in progress. It is also very much worth a look.

Marginal Marks in Book

On Monday Jeffrey P. Barton posted a question on the EXLIBRIS-List concerning how to describe various manuscript annotations to books. Jim Kuhn directed Jeffrey to The Shakespeare Quartos Archive (here), to a fabulous list of manuscript annotations in the “Encoding Documentation” section (here), based on the OED and/or Peter Beal’s Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology (2008).

Marginalia explored. A blog post from our colleagues in the Senate House Library on Philip de Commynes’s The Historie of Philip de Commines Knight, Lord of Argenton, translated by Thomas Danet.

We’re recommending a fascinating blog post from the Houghton Library on bookmarks as evidence of use and reading. The occasion is the library’s acquisition of a copy of Jean Croiset’s La dévotion au Sacre Coeur de Notre-Seigneur Jesus-Christ (Paris, 1741) which contains “embroidered heart-shaped cushion of green silk with five ribbons of different colors” and other ribbons tied to the book.

When the American writer David Markson, the author of Wittgenstein’s Mistress (1988) an d Reader’s Block (1996), died on 4 June 2010, his personal library was in accordance with his wishes donated to The Strand bookstore on Broadway. This New York bookstore, it is said, was a favourite of his. Not soon after a woman named Annecy Liddell bought Markson’s copy of Don DeLillo’s White Noise on the shelves. Not knowing who he was, but fascinated by his increasingly scathing annotations — he seems to have found the novel “boring” — she decided to Google the person who had written his name on the front flyleaf and wrote about her discovery on Facebook. Soon word spread and a small “underground” movement of Markson Treasure Hunters gathered to scour the shelves at The Strand. Now a blog has been set up, Markson Reading Markson, to collect and bring together again the books that have come from Markson’s library.

d Reader’s Block (1996), died on 4 June 2010, his personal library was in accordance with his wishes donated to The Strand bookstore on Broadway. This New York bookstore, it is said, was a favourite of his. Not soon after a woman named Annecy Liddell bought Markson’s copy of Don DeLillo’s White Noise on the shelves. Not knowing who he was, but fascinated by his increasingly scathing annotations — he seems to have found the novel “boring” — she decided to Google the person who had written his name on the front flyleaf and wrote about her discovery on Facebook. Soon word spread and a small “underground” movement of Markson Treasure Hunters gathered to scour the shelves at The Strand. Now a blog has been set up, Markson Reading Markson, to collect and bring together again the books that have come from Markson’s library.

In all 63 boxes of books ended up at The Strand, the result of many weekly rummages by Markson who had lived nearby. Craig Fehrman, who wrote about the library in The Boston Globe, called it a “library left, not lost”, in contrast with the many personal collections that have disappeared from history. The romanticism behind the dispersal of Markson’s books is fascinating, though of course for historians of reading somewhat of a methodological nightmare.

We can confirm (with a fair bit of excitement) that Heather Jackson and Dirk Van Hulle have kindly agreed to give a plenary lecture at the conference.

Marginal note on poverty of magnificent eloquence in Coleridge's copy of A Treatise on Indigence (1806) by Patrick Colquhoun (pp.8-9). Image courtesy Pratt Library, University of Toronto

Heather Jackson is Professor of English at the University of Toronto (Canada). She is the editor of three volumes S.T. Coleridge’s marginalia in the Coleridge Bollingen Collected Works and the author of two excellent books: Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books (2001) and Romantic Readers: The Evidence of Marginalia (2005), both published by Yale University Press. Dirk Van Hulle is Professor of English at the University of Antwerp (Belgium). He is the author of Textual Awareness: A Genetic Study of Late Manuscripts by Joyce, Proust, and Mann (2004) and Manuscript Genetics, Joyce’s Know-How, Beckett’s Nohow (2009), and he has co-edited Reading Notes, a special of Variants: the Journal of the European Society for Textual Scholarship 2/3 (2004). He is currently at work on a digital project and monograph on the library of Samuel Beckett.

For practical reasons, the dates of the conference “Writers and their Libraries” at the Institute of English Studies, University of London were changed. The conference will now take place on 15-16 March 2013.